poem as risk to national security/as terrorist act pt. 1: Guantánamo Bay

June 23, 2013 § 1 Comment

DEATH POEM

Take my blood.

Take my death shroud and

The remnants of my body.

Take photographs of my corpse at the grave, lonely.

Send them to the world,

To the judges and

To the people of conscience,

Send them to the principled men and the fair-minded.

And let them bear the guilty burden, before the world,

Of this innocent soul.

Let them bear the burden, before their children and before history,

Of this wasted, sinless soul,

Of this soul which has suffered at the hands of the ‘protectors of peace.’

— Jumah Al Dossari, Poems from Guantánamo: The Detainees Speak Ed. Marc Falkoff (2007)

The Guardian reported yesterday that the US is escalating tactics to break the current hunger strike at Guantánamo Bay (“US steps up efforts to break Guantánamo hunger strike”). These new, more brutal techniques are said to include “making cells ‘freezing cold to accentuate the discomfort of those on hunger strike'” and “the introduction of ‘metal-tipped’ feeding tubes” into prisoners’ stomachs twice a day, a technique which causes them to vomit. Two-thirds of the detainees who still remain at the prison camp are said to be participating in the strike: there are 166 prisoners still at Guantánamo; 104 are participating in the hunger strike; 44 are being force-fed, a method which violates international medical ethics specified in the World Medical Association’s Declaration of Malta [1].

Jumah Al Dossari, a former detainee at Guantánamo, released in 2007, and the author of “Death Poem,” participated in the first summer hunger strike at Guantánamo in 2005; of this experience he reported to his lawyer the prisoners were willing to die in order to protest the conditions in which they were being held. It has been documented that during his time in captivity Al Dossari tried to kill himself twelve times; once “he was found by his lawyer, hanging by his neck and bleeding from a gash to his arm” (Poems from Guantánamo p.31). US authorities have described such suicide attempts, by Al Dossari and others, as “manipulative self-injurious behavior” (p.2). Marc Falkoff, the editor of Poems from Guantánamo: The Detainees Speak, in which Al Dossari’s “Death Poem” appears, notes that when “three detainees successfully killed themselves in June 2006, the military called the suicides acts of ‘asymmetric warfare'” (p.2).

It’s not surprising then that if a successful suicide can be understood as “asymmetric warfare,” poems written by prisoners at Guantánamo over the years might be characterized by the US military as representing a “special risk” to national security. Amnesty International quotes the Pentagon’s reaction to the publication of this volume of poetry:

While a few detainees at Guantánamo Bay have made efforts to author what they claim to be poetry, given the nature of their writings they have seemingly not done so for the sake of art. They have attempted to use this medium as merely another tool in their battle of ideas against Western democracies. (Defense Department spokesman Cmdr. J. D. Gordon, quoted by Amnesty International Magazine, Fall 2007.)

It also sounds very familiar. In 1933 the poet Osip Mandelstam was taken into custody for writing a poem about Stalin (which has come to be known as the “Stalin epigram”):

We live, deaf to the land beneath us,

Ten steps away no one hears our speeches.

All we hear is the Kremlin mountaineer,

The murderer and peasant-slayer. (p.100 Hope Against Hope)

He was detained in the notorious Lubianka, headquarters of the Cheka, the secret police. Here he was subjected to many of the same techniques used on the Guantánamo Bay captives, such as sleep deprivation, sensory deprivation, humiliation, isolation, a complete cutting off of all that binds a human being to the outside world.

Osip Mandelstam’s wife, Nadezhda Mandelstam, describes how he had even made a contingency plan for carrying out suicide after the inevitable detention by the Cheka, persuading a cobbler to “secrete a few blades” in the sole of his shoe. As with Jumah Al Dossari, Mandelstam attempted suicide by slashing his wrists. Nadezhda writes, on going to visit him there upon his provisional release (on the condition he go into internal exile), “I saw that M. had bandages on both wrists. When I asked him what was wrong with them, he just waved his hands, but the interrogator delivered himself of an angry speech about how M. had brought forbidden objects into his cell — an offence punishable under such-and-such an article. It turned out that M. had slashed his veins with a razor blade.” (p.89, Hope Against Hope).

The parallels continue. Marc Falkoff observes that the majority of the poems written at Guantánamo did not receive security clearance for publication, and remain classified (he is writing in 2007). Many of the poems were confiscated and destroyed before the prisoners could even give the poems to their lawyers. The poems, the military maintain, are a security risk because of their “form and content.” Coded messages might be sent. Poetic language is protean and resists literal interpretations; it can be read in many ways. Falcoff:

Still, the earliest of the poems we submitted for classification review were deemed unclassified, and it was only after the Pentagon learned that we were putting together a book of the poems that the hand of censorship came down. Hundreds of poems therefore remain suppressed by the military and will likely never be seen by the public. In addition, most of the poems that have been cleared are in English translation only, because the Pentagon believes that their original Arabic or Pashto versions represent an enhanced security risk. Because only linguists with secret-level security clearances are allowed to read our clients’ communications (which are kept by court order in a secure facility in the Washington, D.C., area), it was impossible to invite experts to translate the poems for us. The translations included in the collection, therefore, cannot do justice to the subtlety and cadence of the originals. (“Poems from Guantánamo,” Amnesty International magazine, Fall 2007).

Nadezhda Mandelstam notes that Mandelstam’s interrogator, Christophorovich, was known as a “literature specialist.” (p.94) (the equivalent I imagine of a “linguist with secret-level security clearance”):

Christophorivich referred to the poem as a ‘document’ and to the writing of it as a ‘terrorist act.’ At our interview he said he had never before set eyes on such a monstrous ‘document.’ (p.97)

Of the other members of the Cheka, Nadezhda Mandelstam writes,

But the extraordinary thing about those times was that all these ‘new people,’ as they killed and were destroyed themselves, thought that only they had a right to their views and judgements. Any one of them would have laughed out loud at the idea that a man who could be brought before them under guard at any time of the day or night, who had to hold up his trousers with his hands and spoke without the slightest attempt at theatrical effects — that such a man might have no doubt, despite everything, of his right to express himself freely in poetry. (p.96)

The prisoners at Guantánamo would have no difficulty in understanding such a right. Marc Falkoff points out that the need to find human expression for their experiences was so strong amongst the early Guantánamo captives that they wrote their first poems, without having access to pen or paper, on styrofoam cups:

Many men at Guantánamo turned to writing poetry as a way to maintain their sanity, to memorialize their suffering and to preserve their humanity through acts of creation. The obstacles the prisoners have faced in composing their poems are profound. In the first year of their detention, they were not allowed regular use of pen and paper. Undeterred, some drafted short poems on Styrofoam cups retrieved from lunch and dinner trays. Lacking writing instruments, they inscribed their words with pebbles or traced out letters with small dabs of toothpaste, then passed the “cup poems” from cell to cell. The cups were inevitably collected with the day’s trash, the verses consigned to the bottom of a rubbish bin. (“Poems from Guantánamo,” Fall 2007 Amnesty International Magazine).

[1] See “Letters: Stop Guantanamo Bay force-feedings“, The Guardian 16 June 2013. Shaker Aamer, the last remaining British resident of the prison, has alleged that some nurses participating in the force-feeding sessions have stopped wearing name-tags so that they cannot be identified; he also notes one detainee had a feeding tube accidentally placed into a lung, which caused him to cough up blood. The current hunger strike began in February of this year.

“the idyllic era of cushions was at an end”: 20th century lyric genres

June 19, 2013 § Leave a comment

Some twentieth century lyric genres [1]:

1. poem written on cigarette pack lining and buried, Makronisos, Greece, c.1948:

“even under the harshest conditions on Makronisos [an island detention centre for political prisoners after the Second World War], Ritsos was constantly writing, on whatever scraps of paper he could find, including the linings of cigarette packs, which he hid or buried in bottles in the ground” — “Introduction,” Diaries of Exile p.viii Translators Karen Emmerich and Edmund Keeley

1a. variant: poem written on cigarette paper, the Small Zone, Barashevo Labour Camp, Mordovia, USSR, c. 1983:

“In minute letters, I write out my latest poems on four-centimetre-wide strips of cigarette paper. This is one of the our ways of getting information out of the Zone. These strips of cigarette paper are then tightly rolled into a small tube (less than the thickness of your little finger), sealed and made moisture-proof by a method of our own devising and handed on when a suitable opportunity presents itself.” — Grey is the Color of Hope Irina Ratushinskaya p.75

1b. variant: poem placed in glass preserving jar and buried in the garden, by night. USSR, c. Stalinist Russia:

“[Andrei Sinyavski] tells how, at the height of the Stalin terror, Alexander Kutzenov used to seal his manuscripts in glass preserving jars and bury them in his garden at night-time.” —The Government of the Tongue, Seamus Heaney, p.97

2. poem hidden in cushion or saucepan, Stalinist Russia, c.1934:

“I began to make copies and hide them in various places. Generally I put them in hiding-places at home, but copies I handed to other people. During the search of our apartment in 1934 the police agents failed to find poems I had sewn into cushions or stuck inside saucepans and shoes….Voronezh [where Osip served part of his sentence of exile after writing the “Stalinist epigram”] marked a new stage in our handling of manuscripts. The idyllic era of cushions was at an end — and I remembered all too vividly how the feathers had flown from Jewish cushions during Denikin’s pogroms in Kiev. M.’s memory was not as good as it had been, and with human life getting cheaper all the time, it was in any case no longer a safe repository for his work….” — Nadezhda Mandelstam, Hope Against Hope, p.324

3. poem in a burnt notebook, Moscow, c.1938-41

“…suddenly, in mid-conversation, [Akhmatova] would fall silent and, signalling to me with her eyes at the ceiling and walls, she would get a scrap of paper and a pencil; then she would loudly say something very mundane: ‘Would you like some tea?’ or ‘You’re very tanned’, then she would cover the scrap in hurried handwriting and pass it to me. I would read the poems and, having memorized them, would hand them back to her in silence. ‘How early autumn came this year,’ Anna Andreevna would say loudly and, striking a match, would burn the paper over an ashtray…” — Lydia Chukovskaya, The Akhmatova Journals Volume 1, 1938-1941, (p.6)

“Working on the night shift and running between one machine and another in the enormous shop, I kept myself awake by muttering M.’s verse to myself. I had to commit everything to memory in case all my papers were taken away from me, or the various people I had given copies to took fright and burned them in a moment of panic — that had been done more than once by the best and most devoted friends of literature. My memory was thus an additional safeguard — indeed, it was indispensable to me in my difficult task. I thus spent my eight hours of night work not only spinning yarn but also memorizing verse.” — Nadezhda Mandelstam, Hope Against Hope p.411-2

5. poem scratched onto Styrofoam cup, Guantánamo Bay, early 21st century:

“Many men at Guantánamo turned to writing poetry as a way to maintain their sanity, to memorialize their suffering and to preserve their humanity through acts of creation. The obstacles the prisoners have faced in composing their poems are profound. In the first year of their detention, they were not allowed regular use of pen and paper. Undeterred, some drafted short poems on Styrofoam cups retrieved from lunch and dinner trays. Lacking writing instruments, they inscribed their words with pebbles or traced out letters with small dabs of toothpaste, then passed the “cup poems” from cell to cell. The cups were inevitably collected with the day’s trash, the verses consigned to the bottom of a rubbish bin.” — “Poems from Guantanamo” Amnesty International Magazine Fall 2007

5a. variant: poem burnt onto bar of soap with matchstick, and then memorised, the Small Zone, Barashevo Labour Camp, Mordovia, USSR, c. 1983 Irina Ratushinskaya (see also Pencil Letter, Bloodaxe Books, 1988).

[1] See “The Death of the Book à la russe: The Acmeists under Stalin,” a chapter in Clare Cavanagh’s Lyric Poetry and Modern Politics: Russia, Poland, and the West.

Miklós Radnóti’s Bor Notebook

March 19, 2013 § Leave a comment

Postcard (3)

The bullocks’ mouths are drooling bloody spittle,

all the men are pissing blood,

our squadron stands in rough and stinking clumps,

a foul death blows overhead.

Mohács, 24th Oct. 1944

translation by Francis Jones, Camp Notebook (2000)

The mass grave near the village of Abda, Hungary, where the poet Miklós Radnóti was buried on 4 November 1944 after a horrific forced march from the Bor labour camp, was exhumed after the war, in June of 1946. Radnóti’s body was identified by a notebook, along with several identification papers, carried in his clothes. From the “Coroner’s Report on Corpse No.12”:

A visiting card with the name Dr. Miklós Radnóti printed on it. An ID card stating the mother’s name as Ilona Grosz. Father’s name illegible. Born in Budapest, May 5, 1909. Cause of death: shot in the nape. In the back pocket of the trousers a small notebook was found soaked in the fluids of the body and blackened by wet earth. This was cleaned and dried in the sun.

— Cited in the introduction to Under Gemini, a selection of the poetry and prose of Miklós Radnóti.

The notebook measures 14.5 x 10 cm; it is square-ruled, with 30 leaves. A facsimile of the notebook, known as the Bori Notesz or Bor Notebook, can be seen online (Bor Notebook): each page has been reproduced, showing the slightly blurred, black-inked letters which fade almost to a blue mist towards the bottom of the notebook where it seems to have been most badly soaked in fluids.

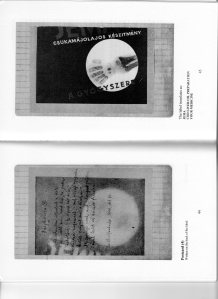

The final razglednica or postcard poem (‘razglednica’ is Serbian for ‘postcard’) was written by Radnóti on the back of a medicine label for cod liver oil: the label is a striking white circle within a rust-coloured rectangle; within the white circle the image of X-rayed finger and wrist bones appear. The label itself was then inserted by Radnóti into two pages of the notebook, which, once wet, also transferred a faint stain of the label’s image onto those pages, so that it creates a ghostly palimpsest of the X-rayed hand and the third razglednica where he describes the men “pissing blood” and death carried on the wind.

Images from Camp Notebook. Arc Publications, 2000.

Emory George tells us in his introduction to the Collected Poems that Radnóti acquired the notebook in the Bor camp from a local farmer who was allowed to sell food and cigarettes to the prisoners at the work sites, and argues that Radnóti used the notebook sparingly — that he must have composed most of the lines in his head as he laboured through the day, or at night in the barracks, only writing down a line or a poem once it was complete. You can see this in that the poems seem to be neatly copied out; there are no words crossed out or lines revised, beyond the insertion of whole stanzas by means of arrows or stars. Several of the poems in the notebook he managed to pass along on a separate sheet of paper to another prisoner in the camp, Sándor Szalai; the poems he gave to Szalai were “The Seventh Eclogue,” “The Eighth Eclogue,” “À la recherche…,” “Letter to My Wife,” and “Forced March.”

When the camp was disbanded, and prisoners were being divided up into two groups, the first column to leave immediately, Radnóti was placed with Szalai in the second column. There were rumours that those in the second column would simply be killed outright. Radnóti entreated the guards to be allowed to go with the first column. As Zsuzsanna Ozsváth observes in In the Footsteps of Orpheus, “That was his tragedy. For the second column stayed in Bor until September 29, and when it finally set out, it was attacked by a group of partisans who liberated the servicemen” (p.213). Szalai, being in the second column, then arrived in Temesvár and in fact managed to have two of Radnóti’s poems (“Seventh Eclogue” and “À la recherche”) published in October 1944, when Radnóti was still alive and enduring the final forced march of the first column which would end in his death.

Here is the last postcard, in which he describes the execution of the musician Miklós Lorsi:

Postcard (4)

I tumbled beside him, his body twisted and then,

like a snapped string, up it sprang again.

Neck shot. “This is how you’ll be going too”,

I whispered to myself, “just lie easy now”.

Patience is blossoming into death.

“Der springt noch auf,” rang out above me. Mud

dried on my ear, mingled with blood.

Szentkirályszabadja, 31st Oct. 1944

Translation by Francis Jones, Camp Notebook

This final razglednica was only recovered and published after his body was exhumed in 1946.

Radnóti had made some provision for preserving these last poems. On the first two pages of the notebook, repeated in Hungarian, Serbo-Croatian, German, French, and English, he had written the following:

This notebook contains the lyrics of the Hungarian poet Miklós Radnóti. Please send it to Hungary to the address of Dr. Gyula Ortutay, University Lecturer, Budapest, VII, Horánszki utca 1.I.

chronology of the last days of Miklós Radnóti

March 13, 2013 § Leave a comment

The column of 3600 men sets out from Bor on 17 September 1944. They march by day and camp in the fields by night. A man is shot for leaving the road to urinate in the ditch; another for going into the fields to pick some corn. They have little to eat—bread, marmalade, a little soup; less and less; raw carrots, squash. More men are shot for picking corn. A German militia unit joins the guards and things become much worse. Hundreds are executed on the road. Radnóti’s feet open with wounds. Abscesses in his mouth. At Ujvidék they boil straw to eat.

On 6 October he writes the second Razglednica, or ‘Picture Postcard.’ He has been on the forced march now for 21 days.

On 7 October the column is divided into two groups. The first group of 1000 men is taken to a large pit at Cservenka’s brickyard and shot in groups of 20 by SS troops. The killing stops at dawn. The second group, of which Radnóti is one, meets up with a troop of SS on horseback. They make the men lie down on the road and shoot them at random. The ditches swell with corpses and yellow stars. Miklós Lorthy, who has been shot, tries to rise up and continue marching with the help of Radnóti and another man. An SS man calls out, Der springt noch auf! and shoots him again. On 14 October they arrive at a tanning yard in Mohács and stay for weeks, unloading towboats. The men are urinating blood, a sign that the body is now consuming itself.

Radnóti writes the third Razglednica on 24 October.

They travel by boxcar to Szentkirályszabadja. He writes the final Razglednica on 31 October, on the back of a medicine bottle label for cod liver oil.

During the day’s march the guards begin to make the men run; those who collapse are shot. 6 November Radnóti is beaten—deep gashes to his face and head—at Pannonhalma. On 8 November, twenty-two of the men, including Radnóti, are placed on horse-drawn carts and taken to a hospital, but turned away as there is no room for them. So the two guards take them to a field near a dam on the Rabca River. They borrow a hoe from a local inn, tools from the dam-keeper’s wife, and tell the men to dig a hole—but they are too weak. The guards dig the hole instead, and make several men jump in to smooth out the floor. Then the guards shoot the twenty-two men, one by one. They cover their bodies with soil, and return the tools and the hoe.

The details of this chronology are taken from Zsuzsanna Ozsváth’s In the Footsteps of Orpheus.

the poem as trace of an event 2

February 28, 2013 § 2 Comments

Five miles away the hayricks and houses

are going up in fire;

beside the fields, peasants smoke their pipes

in silence and in fear.

Here, the lake still ripples at the little

shepherdess’s stride;

on the water a ruffled flock of sheep

stoops to drink a cloud.

Cservenka, 6th Oct. 1944

— “Razglednica (2)” (Postcard 2), Miklós Radnóti, transl. Francis R. Jones

Beyond local, small-scale ecological witnessing, such as that of Borodale, Oswald, Longley, (discussed in “the poem as trace of an event 1“) some poets become directly caught up in larger historical events, these bloody trajectories of the 20th and 21st centuries, events which are then registered in their poetry in various ways — or sometimes deliberately resisted: Czesław Miłosz, on refusing permission to reprint some of his poems on the Warsaw Uprising: “I do not want to be known as a professional mourner.” (See his interview in The Paris Review.)

What kind of knowledge might a poem carry of an event such as that of the Hungarian poet Miklós Radnóti’s forced march of early November 1944, a march which ended in his execution in a mass grave?

Even during this march Radnóti managed to continue to write small poems in a soft-covered notebook, now known as the “Bor Notebook,” or sometimes “Camp Notebook.” (An online facsimile of it can be found here, from a 2009 exhibit of his work.) This was a small, square-ruled notebook which was later found on his body when the grave where he had been buried was exhumed after the war. [1]

Perhaps the very question is wrong, suggesting a desire for some utility for poetry, a desire that we can trace back in the English tradition at least to Sir Philip Sidney’s Defence of Poesy (published 1595), who argued that poetry should both teach and delight, and which finds expression today in the “ethical turn” in literary studies. David-Antoine Williams offers an informative overview of this ethical turn in chapter 1, “Ethics, Literature, and the Place of Poetry,” of his Defending Poetry: Art and Ethics in Joseph Brodsky, Seamus Heaney, and Geoffrey Hill (2010). Tellingly, he notes that the focus of this ethical turn has been on narrative. Williams observes,

“Many writers on the ethics of literature simply ignore poetry and the poetic altogether: if the neo-Aristotelian didactic and the responsibility-oriented deconstructive streams of ethical criticism share anything, it is that both rely on broad theories of narration, which is to say they regard real or imagined human actions, consequences, and fates (usually) within social situations. It is the narrative components of novels, stories, dramas, etc. that are discussed and debated over, not, usually, their formal effects […] it is unclear where narrative-dependent ethical criticism leaves poetry, especially lyric poetry. Attempts to account for an ethics of poems are often perforce drawn back to narration: Susan Gubar, in discussing recent Holocaust poetry, ultimately locates its ethics in its ability ‘to counter the numbing amnesia inflicted on its casualties by traumatic injury and on their descendants by our collective overexposure to widely circulated narratives of attrocity.’ In other words, poetry’s ethicity depends on the extent to which its narratives can replace or refresh old, worn ones. Unsurprisingly, Gubar’s analysis never lingers on anything non-narrative, formal, or even ‘poetic’ in the poetry she treats.” (p.18)

So when I ask what knowledge a poem such as Radnóti’s “Razglednica (2)”, which I quoted above, might carry, I am thinking of knowledge and an ethical force beyond that which narrative holds. In any lyric poem we find both narrative and lyric elements, where the lyric often bears a heightened focus on language’s own procedures, by means of its formal elements. Williams is pointing here towards these procedures and formal qualities, and how they might be associated with a poem’s “ethicity”.[2]

An initial difficulty in concentrating upon “Razglednica (2)” as a lyric poem is its contextual history. Note that the poem is always published with the place and date of its writing — Cservenka, 6th Oct. 1944; Radnóti was on the forced march by this time. The original notebook includes these details of place and date following each poem, as if a “signature;” all versions of the poems in translation I have read follow him in this. And this signature invites us to always read the ‘postcard’ — ‘razglednica’ is the Serbian word for ‘postcard’ — within the context of his lived history and witnessing, as if each postcard-poem describes an image or snapshot from the march, the ghostly “reverse” of the poem; the notebook itself is often described as a witness from beyond the grave. But does this then relegate his razglednici to mere documentary snapshots of his own slow torture and death? They are often read as transcription or witness of these events, analogous to a newspaper report, as in the final razglednica, where he describes the killing of an acquaintance, which could also be a postcard documenting his own execution several weeks later. Yet what remains then of its status as lyric poem?

“Razglednica (2)” is the second of four such postcard-poems he wrote in the last months of his life. In them Radnóti invokes the pastoral tradition. He was a trained classicist, and some of his work consisted of making translations of Virgil, among others; Radnóti’s finest poems I think are his own “Eclogues,” which incorporate this Virgilian mode of social critique and lament with elements drawn directly from his experiences during the war — for example, in the Second Eclogue, instead of staging a dialogue with a peasant, he speaks with a military pilot who conducts bombing raids by night: “Pilot: Went far out into the night; I laughed, I was so mad./Like swarms of bees the fighter planes buzzed overhead…” (Transl. Emory George, p.230).

Similarly in “Razglednica (2),” the war is invoked; the image of a flock of sheep which stoops to sip from a cloud-reflecting lake is framed by the five-mile-distant carnage of a village in flames. There is no significant narrative here; merely ironic juxtaposition of two images. I take pleasure in his description of the lake as if the sheep stoop to sip from a cloud, in his having taken note of this trompe l’oeil effect, presenting a verbal equivalent by means of metaphor. The invocation of the pastoral also invites us to consider the function of this lyric mode, and its very capacity to document or engage with the events of war, which it seems here to do most forcefully.

But I am still avoiding the issue of the formal qualities of the poem, as much as I can engage with them in a translation, not being able to read the original Hungarian. Radnóti often used classical and closed forms; the razglednici are written in quatrains, and employ cross rhyme; some of his translators attempt to offer similar formal patterns, while the Polgar, Berg, and Marks translation employs free verse. The decision to replicate the formal patterns is important, however, for his poems use these formal elements of poetry to stand against the chaos and unmaking of war. During the years of the war he made the deliberate choice of turning to classical structures, even though his earlier collections of poetry experimented with free verse; he seemed to have found strength in this formal patterning, so much so that he did not stop writing these poems, even under duress, as if the closed structures helped to order and contain the violence he witnessed.

Emery George’s 1980 translations of the entire corpus of Radnóti’s poetry attempt to preserve many of the formal qualities of Radnóti’s verse, as do the more recent translations by Zsuzsanna Ozsváth and Frederick Turner in their 1992 Foamy Sky: The Major Poems of Miklos Radnóti, and Francis R. Jones in Camp Notebook (2000). George notes he tries to follow Radnóti’s own translation principles:

“It would not do […] to render a hexameter work in ‘open’ form, any more than it would do to try to render it in Alexandrines or in blank verse. Every syllable contributes its share of the weight to careful work in meter or in the shaped line and stanza. Indeed fidelity requires that, wherever similarities in syntax permit it, even the relative positions of words be observed; that where lexicon and semantics favor it we show sensitivity to the possibility of sound repetition somewhere near the passage that exhibits it in the original […] In short, the translator of poetry had better have a good ear.” p.42]

He introduces all kinds of questions here regarding translation, but I want simply to note his insistence on the importance of form to Radnóti himself as translator and poet.

Here is George’s own translation of “Razglednica (2)”:

Nine kilometers from here the haystacks and

houses are burning;

sitting on the field’s edges, some scared and speechless

poor folk are smoking.

Here a little shepherdess, stepping onto the lake,

ruffles the water;

the ruffled sheep flock at the water drinks from

clouds, bending over.

The rhyme scheme, which both Jones and George preserve by means of slant rhyme is xaxa xbxb. Jones rhymes fire and fear, stride and cloud, while George strains towards burning/smoking, and water/over. Rhyme often reinforces semantic or emotional connections between words. In this, I find Jones’ translation more successful in the linking of fire to fear; the ambiguity of George’s poor folk ‘smoking,’ as if smouldering and not smoking a pipe, is unfortunate.

The two quatrains are used by Radnóti to set up two distinct images which contrast sharply and ironically with one another. In the first quatrain we see the distant, burning village and the peasant observers — and are perhaps reminded that we also watch, as from a great distance, this scene from almost seventy years ago. In the second quatrain a more typical pastoral image is presented of a shepherdess with her flock of sheep, which sip from the sky-reflecting lake. The ironic juxtaposition of the two images is strengthened by the formal elements of the first quatrain (alternating rhyme, line length) which are then mirrored in the second, as cloud is mirrored in lake, as the first image begins to obscure or cloud over the second as the war progresses.

George more successfully captures the rhythm of the original line, I suspect, with his use of a triple foot and falling rhythm. But I like the way in which Jones manages by means of enjambment to emphasize fire, silence, and fear in lines 2 and 4 of the first quatrain:

Five miles away the hayricks and houses

are going up in fire;

beside the fields, peasants smoke their pipes

in silence and in fear.

The first line with its reference to hayricks might be the opening of a simple pastoral quatrain, until the second line undercuts this with the words “are going up in fire.” Similarly, peasants smoking their pipes, another idyllic image, is quickly undercut by “in silence and in fear.” I don’t know if this effect is present in the original, but it is effective.

The very fact that Radnóti writes this poem while on a forced march, using elements such as metre and rhyme, quatrain form, image, metaphor, and the resultant compression of language this entails, can also be read as significant: he makes pattern out of a chaos of sound, a poem out of the chaos of war which, as Scarry observes in The Body in Pain, unmakes language along with many other human institutions. This tiny poem functions as counterforce to such destruction.

Similarly, I equally value in Radnóti’s poems from his Bor Notebook the gesture of the individual voice, the single, quiet voice that speaks in the silence, in the dark. As readers, we are allowed access to the imprint of his single consciousness — again an imprint that is found in the very formal qualities of the poem itself, a transcription of what this man thought as he rested in barracks (I don’t mean here a spontaneous trace of his conscious thought, but inevitably a re-presentation of this thought through formal means; Grossman–“Poems are fictions of the privacy of other minds. Wherever the philosopher says per impossibile the poet shows the way” p.147 Summa Lyrica), as in the magnificent “Seventh Eclogue” in which he describes a dream-journey from the forced labour camp back to his home:

from “Seventh Eclogue”

Look how evening descends and around us the barbed-wire-hemmed, wild

oaken fence and the barracks are weightless, as evening absorbs them.

Slowly the glance loses hold on the frame of our captive condition,

only the mind, it alone is alive to the tautness of wire.

See, Love: phantasy here, it too can attain to its freedom

only through dream, that comely redeemer who frees our broken

bodies — it’s time, and the men in the prison camp leave for their homes now.

(translation by Emery George, in The Complete Poetry)

Radnóti is using here the classical dactylic hexameter line, one which we are much less used to hearing in English, and which George attempts to reproduce — he speaks of Radnóti’s hexameter lines as having “grace, speed, and power” (p.42).

While Virgil uses hexameter lines to write the Eclogues, and this may be Radnóti’s more immediate model, we might consider also the use of the hexameter line as formal vehicle in epic poetry, foremost of which is the Iliad. In Susan Stewart’s Poetry and the Fate of the Senses (2002) she makes the useful distinction between the epic mode, which carries official ideologies, the state’s version of war, and the lyric mode, which, she argues, offers the perspective of the individual caught up in war, and carries traces of an individual’s sense-perceptions and emotions (p.296). Radnóti in his use of the hexameter line to write many of his last poems we might read as an undermining of this vehicle of official ideology; he uses it to convey the individual’s first-person experience of sensation and emotion, a private dream life in the midst of war. Frederick Turner in his translator’s essay in Foamy Sky, also notes the importance of this hexameter line in Radnóti’s poetry: “..the epic/pastoral hexameters of the first and eighth eclogues are fundamental to their meanings, recalling the power of Homer, the moral complexity of Virgil, and that strange Hadean combination of the arcadian and the heroic that we associate with the descent to the land of the dead” (p.xlvii).

Formal qualities are integral to the effect Radnóti seeks to achieve in these last poems. George acknowledges the documentary or trace aspect of Radnóti’s Bor poetry, and yet insists on their self-conscious attention to making:

“If ever there was art that moves beyond the naturalistically faithful documentation of life that it appears to be providing, it is the poems of the Bor Notebook. To be sure we have no reason not to accept at face value some of the conditions the poems depict, or — nearly so — some of the statements they represent a man as making. That the poet misses [his wife] Fanni and that he hopes to make superhuman attempts to return to her (“Seventh Eclogue,” “Letter to My Wife,” “Forced March”), that in the solitude of his brutish exile he is consoled by his thoughts (“Letter to My Wife,” “Eighth Eclogue”), that in the midst of his own predicament he is thinking of the many who have already met their fates in one form or another (“A la recherche….”) […] What may still need our attention is secrets of the poems not revealed by the images alone” (p.39).

George then goes on to note the deliberate invocation and undercutting of the pastoral, and the formal skill of the Bor poems, bearing “a hardness and diamond-like perfection” (p.40) In this, he is directing our attention to the formal over the documentary “trace” of this poetry.

Yet he also points out that the “Razglednica” as imitation “postcard” is part of a longer experimental tradition by Radnóti to engage with “letters, diary entries, newspaper reportage, expansions of poetic expression that parallel concrete and three-dimensional poetic happenings in our time” (p.40). Here Radnóti would seem to self-consciously engage with poem as documentary trace of an event.

[1] The Bor notebook comprised the 7th and 8th Eclogues, “Root,” “Letter to my Wife,” ” À la recherche,” “Forced March,” as well as the four Razglednici or postcard poems.

[2] Williams’ comment on Gubar and the role of narrative in poetry is not entirely fair. Consider her discussion of “Why poetry matters” in chapter 1 of Poetry After Auschwitz: “poetry serves an important function here, for it abrogates narrative coherence and thereby sparks discontinuity […] In an effort to signal the impossibility of a sensible story, the poet provides spurts of vision, moments of truth, baffling but nevertheless powerful pictures of scenes unassimilated into an explanatory plot and thus seizes the past ‘as an image which flashes up at the instant when it can be recognized and is never seen again.’ According to Benjamin, images (not stories, which tend to recount the past so as to account for it) put the ‘then’ of the past into a dialectical relationship with the ‘now’ of the present, constitute a critique of the myth of progress, and promote mindfulness about how the past continues to exist as an outrage in the present.” p.7 That being said, however, I agree with him that in her actual treatment of individual poems, she glosses over more formally interesting poems by Celan, Forche, and others, concentrating largely on narrative-driven poetry, which she then herself critically narrates.

the poem as trace of an event 1

February 19, 2013 § Leave a comment

Many of the poems I currently gravitate towards are those which have a documentary aspect: poems that transcribe an event, a thought, an experience, however fleeting. I confess to a belief in, or desire for, sincerity as a moral constraint on poetry; I’m less moved by poetry that dissembles, ventriloquizes, makes up. I want to insist upon a connection between lyric I and poet, however mediated it may be; this is perhaps against the current of a 20th/21st century poststructural critical imperative to cleave the two, which often severs agency and intention from poet. The poem then that I find most compelling can be read, at least on one level, as linguistic trace of an event that has been observed and experienced by the poet.

An example of this is Ted Hughes’ wonderful Moortown Diary, consisting of a series of “notes”/poems which record his experiences working on his farm in Dartmoor in the early 1970s. He tells us in the preface that he used verse as a form because

“In making a note about anything, if I wish to look closely I find I can move closer, and stay closer, if I phrase my observations about it in rough lines. So these improvised verses are nothing more than this: my own way of getting reasonably close to what is going on, and staying close, and of excluding everything else that might be pressing to interfere with the watching eye. In a sense, the method excludes the poetic process as well” (x).

He then describes being asked once to provide an editor of a magazine with one of these poems, or “notes,” and realizing that although it was raw, he couldn’t rework it without having to “translate” it, thus destroying the original in the process. The original he now saw as “the video and surviving voice-track of one of my own days, a moment of my life that I did not want to lose […] Altering any word felt like retouching an old home movie with new bits of fake-original voice and fake-original actions” (xi). He describes the process of poetic revision as if the introduction of corruption, (“fake-original voice,”) a dubbing over of the raw event, or rather, the trace of this raw event. As if the original note were a snapshot or rubbing, still bearing molecular traces of the experience. I think this is a true description of the experience of writing the first draft of a poem, when the words are still freshly inked.

Here is an excerpt from “Ravens,” on a still-born lamb. Hughes describes how the ravens are eating the lamb’s corpse; this note is framed by the interest of a young child accompanying him in the field. We are asked to see through the child’s eyes.

Now over here, where the raven was,

Is what interests you next. Born dead,

Twisted like a scarf, a lamb of an hour or two,

Its insides, the various jellies and crimsons and transparencies

And threads and tissues pulled out

In straight lines, like tent ropes

From its upward belly opened like a lamb-wool slipper,

The fine anatomy of silvery ribs on display and the cavity,

The head also emptied through the eye-sockets…

The note-like quality doesn’t exclude technique: the use of simile (“like a scarf,” “like a lamb-wool slipper”); the very fine use of metaphor to describe the multiplicity of texture of the drawn-out lamb’s “insides” (jellies, crimsons, transparencies, threads, tissues, tent ropes); the use of polysyndeton, that is, consecutive conjunctions (“jellies and crimsons and transparencies”) so that the cumulative list sounds like a child’s chanted enumeration.

I like his description of these “notes” as being about moving close and staying close: his insistence on paying attention. It suggests a moral dimension to the raw or transcript poem: a paying attention to the world as it is, as it is perceived; to perceive and then document what is seen as closely as possible then becomes a way of sharing that knowledge with others through the lens of the poem.

And inevitably with each poet there is a different kind of seeing; each poem also carries a trace of the poet’s mind with its idiosyncratic ways of viewing and interpreting the world.

More recently in the UK, Alice Oswald’s Dart (2002) and Sean Borodale’s Bee Journal (2012) seem to participate in this kind of documentary project, written at the ‘source’ and aiming for an almost anthropoetical or ecopoetical description.

In Dart Alice Oswald made a transcription of the “songlines” of the River Dart, “from the source to the sea.” At one level we can read it as aural history/transcript of the riverflow of voices; we hear echoes of those fishers, poachers, naturalists she met along the river; and beneath this, a deeper folk song that seems to emerge from the waters — “Dart Dart/Every year/Thou claimest a heart.” Here is a brief excerpt:

[forester]

and here I am coop-felling in the valley, felling small sections to

give the forest some structure. When the chainsaw cuts out the

place starts up again. It’s Spring, you can work in a wood and

feel the earth turning

[waternymph]

woodman working on your own

knocking the long shadows down

and all day the river’s eyes

peep and pry among the trees

when the lithe water turns

and its tongue flatters the ferns

do you speak this kind of sound:

whirlpool whisking round?

There is something of witchy Shakespearean song in her poetry, a voice that Woolf also channeled, most notably in Between the Acts. This contrasts strongly with many of the other voices, such as that of the forester above, who speaks of his work in shaping the forest in a more precise, technical register. Many of the voices in fact come from river and forest caretakers, people who watch and listen closely; the poem at one level functions as audiograph of these voices.

If Dart is an audiograph, Sean Borodale’s Bee Journal functions as a bee-keeper’s notebook, charting the progress of a hive. We are told on the volume’s dust jacket that the “poems were written at the hive wearing a veil and gloves, and the journal is an intrinsic part of the kinetic activity of keeping bees.” All of the poems include a date, and sometimes only a date, in the title, in keeping with the journal-like function of the poems. For example, this is from the opening poem, “24th May: Collecting the Bees:”

He just wears a veil, this farmer, no gloves

and lifts open a dribbly wax-clogged

blackwood box.

We in our whites mute with held breath.

Hello bees.

Drops four frames into our silence.

The air is like mica

ancient with thin flecks;

distance viewed through a filter of thousands.

I am observed.

Each box has the pulsar of its source. Porous with eyes

we wait in the spinning sun. The light is Medusa,

sugar of frayed threads; a mesh, a warp-field, all

the skin of our heads.

Here is a similar use, as in Hughes’ Moortown Diary, of the lineation of verse to make notes, and to frame the poet as observing ‘eye’/I. And as also with Hughes, close observation and careful description become paramount: bee-filled air “like mica/ancient with thin flecks” (what a beautiful image, to describe the frames of light-filled, bee-filled air as a slice of flecked stone); the boxes of bees like pulsars, an image which evokes light and sound as pattern, the thrum of energy emitted from each box; the layering of metaphor as if making attempt after attempt at a thick description of the bee-filled light: Medusa; mesh; warp-field.

I imagine all of these poets tracing at least one ancestral line back to the poetry of Edward Thomas, many of whose poems document knowledge of the countryside, such as folk song, herbal and floral lore, place names, and dialectical words, which also carry knowledge. Even the auditory patterns of local voices are consciously recorded in his poems, the “sound of sense” which he and his intimate friend Robert Frost often discussed during Frost’s year in England before the First World War. (See Matthew Hollis’s richly detailed Now All Roads Lead to France for an in-depth discussion of this friendship and its workings on their poetic practices).

I want also to mention Geoffrey Hill’s amazing Mercian Hymns in this context, each hymn, or verset — to use Borodale’s phrase, like “mica/ancient with thin flecks” — requiring a stratigraphical reading of his lines, which document the archaeology and ancient history of Mercia through the 1930s & early 1940s of Hill’s own childhood.

Michael Longley it seems to me also works in this vein, through the minute accumulation of closely-observed detail in Carrigskeewaun. Any individual poem in one of his collections may seem microscopic in its focus, yet the cumulative effect is a moral one, of an intelligence that is paying attention to a small corner of the natural world and sharing it with others. He tells us of his lyric poems on local flowers and birds in Carrigskeewaun as a counter to the Troubles of his native Belfast: “I want the light from Carrigskeewaun to irradiate the northern darkness.”[1]